Dora Maar

1907 – 1997, Paris, France

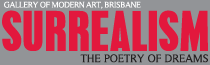

Untitled (Oneiric) 1935

Gelatin silver print from celluloid negative, heightened with crayon

23.5 x 29.4cm

Purchased 2004

AM 2004-164 (27N)

Collection: Musée nationale d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou

© Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN/Philippe Migeat

© Dora Maar/ADAGP. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

Maar studied photography and painting at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux–Arts, and with the encouragement of her mentor, Emmanuel Sougez – a leading figure in the New Photography movement in France – she embarked on a photographic career. Inspired by Sougez’s belief in photography as an experimental medium for modern art, Maar became closely affiliated with the surrealists through her involvement with activist groups, such as Appel á la lutte, Masses and Contre–attaque. The unofficial photographer of the city’s avant–garde, Maar captured iconic images of contemporary literary and artistic figures, including Jacques Prévert, Yves Tanguy and André Breton, and Paul Éluard and wife Nusch.

Untitled (Oneiric) is a composite image made from a montage of two photographic negatives to create a single, dreamlike work. The particular combination of figures and architecture evokes the inexplicable tenor of dreams or hallucinations, as well as the mysterious juxtapositions characterising the surrealist aesthetic. Maar’s skill with montage and composite effects, including distorted perspective, anthropomorphic figures and obscure juxtapositions of contemporary and mythic references, created some of the defining photographs of Surrealism.

Salvador Dalí

1904 – 1989 Figueres, Spain

Hallucination partielle. Six images de Lénine sur un piano (Partial hallucination: Six apparitions of Lenin on a piano) 1931

Oil and varnish on canvas

114 x 146cm

Purchased by the State and accessioned 1938

Collection: Musée national d’art modern, Centre Pompidou, Paris

AM 2909 P

© Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN/Jacques Fajour

© Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala–Salvador Dali/VEGAP. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

Salvador Dalí arrived in Paris from Spain in 1929, and was quickly welcomed into the surrealists’ inner circle. At this time, André Breton was steering the movement towards a phase of political radicalisation aligned to the French Communist Party, of which most surrealists were members. There was great conflict and debate focusing on the revolutionary capacity of art, in particular, because the French Communist Party rejected the idea, advocated by Dalí, that the liberation of desire could play a role in political revolution.

Hallucination partielle was painted at the height of this tumultuous time. Dalí insisted that the image came to him one evening before falling asleep, pre–formed by his unconscious mind. It typifies the artist’s ‘paranoiac–critical’ method, which privileges ‘paranoiac’ thoughts (obsessive, repeating imagery ‘erupting’ from the unconscious) over passive ‘automatic’ thoughts.

The painting depicts a grand piano in a darkened room with a formally dressed grey–haired man seated before it, turning away from the viewer towards a half–open door. Ants crawl over the sheet music and, on the keyboard, small effigies of the late Russian Revolutionary leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, glow as if haloed. The piano is a recurring motif in Dalí's work of this period, and has been interpreted as symbolising bourgeois, ‘family’ values – values Dalí wanted to overturn. The piano appears defiled by the carcass of a rotting donkey in Un chien andalou, the film by Luis Buñuel and Dalí being screened nearby.

Dalí's association with ‘orthodox’ Surrealism was actually short–lived. His equation of Lenin with an authoritarian father figure, which he did most succinctly in his painting The Enigma of William Tell 1933, led to his expulsion from the surrealist group in 1933.

Victor Brauner

1903 Piatra Neamt, Romania – 1966 Paris, France

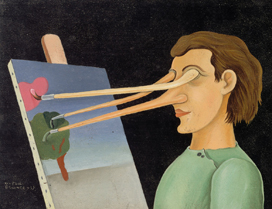

Sur le motif ('Copied from nature') 1937

Oil on wood (oak)

14 x 18cm

Donation of Jacqueline Victor-Brauner 1982

Collection: Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne

AM 1982-117

© Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN /Philippe Migeat

© Victor Brauner/ADAGP. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

‘Sur le motif‘ can be translated as ‘on the spot‘; although, in an art historical context, it is more often translated as ‘copied from nature‘. It refers to a method of painting in which the subject of the painting (figure, still life, landscape) is literally right in front of the painter‘s eyes, sharing the same time and space.

This curious little painting short–circuits a stage in the process of perception, in which the eye sees and the mind interprets. Here, the brushes are literally working as eyes, ‘seeing’ and painting at the same time; however, a pink cloud suggests that this is not as straightforward as it might seem. (The figure’s nose also becomes a paintbrush, suggesting other senses are involved in painting, not just sight).

The eye was an important and recurring theme in Surrealism (as evidenced in the nearby works by Dora Maar and the film Un chien andalou). Eyes were of particular significance to Victor Brauner; in 1931, he painted Self–portrait with Enucleated Eye (Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou), in which his right eye has been gouged out. Brauner’s reputation as a kind of ‘visionary’ was cemented when, seven years following the creation of this work, he was hit in the face with a broken bottle – during a fight in which he was not actually involved – resulting in the loss of his left eye.

Alberto Giacometti

1901 Stampa, Switzerland – 1966 Chur, Switzerland

Table 1933/1969

Bronze

143 x 103 x 43cm

(Unique edition cast at the request of the MNAM

in 1969, after the original plaster of 1933)

Purchased 1969

Collection: Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne

AM 1705 S

© Alberto Giacometti/ADAGP.

Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

This astonishing sculpture was originally created in plaster for inclusion in an important surrealist exhibition held in Paris, in June 1933. It was cast in bronze, in 1969, at the request of the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou. In its original installation, Table was placed against a wall, reinforcing its character as a piece of furniture. Indeed, the work was acquired at the end of the 1933 exhibition by the Vicomte de Noailles, a major patron of the surrealists, and placed in the hallway of his home.

The table’s oddly shaped legs seem too thin to support the veiled female figure resting on one edge. With a neck shaped like a piece in a chess set, this apparent clairvoyant sits before an alchemist’s mortar, a polyhedral shape suggesting a crystal and a severed hand. Her face appears caught in an expression of surprise, but emptiness and melancholy are also present: her blank eyes suggest blindness, or perhaps she ‘sees beyond’ what is before her. The figure of the aveugle – the blind manor woman – recurs in many of Giacometti’s drawings of this period, and would become a conceptual and visual feature of his oeuvre for decades to come.

Alberto Giacometti

1901, Stampa, Switzerland – 1966, Chur,

Switzerland

Femme égorgée

(Woman with her throat cut) 1932/1940

Patinated bronze

21.5 x 82.5 x 55cm, ed.2/5

(Alexis Rudier foundry, France)

Purchased with the support of the

Fonds du Patrimoine, 1992

Collection: Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne

AM 1992-359

© Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN /Philippe Migeat

© Alberto Giacometti/ADAGP.

Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

Femme égorgée is the most disturbing and complex object produced during Alberto Giacometti’s surrealist period. This bronze version, cast in 1940, was originally in the collection of art dealer Pierre Matisse; Giacometti exhibited at Matisse’s New York gallery in the late 1940s.

Femme egorgée presents a body violated, its back arching as if screaming in agony or ecstasy. In explaining the work to Matisse, Giacometti pointed out ‘the carotid artery slit’, which can be discerned on close inspection of the sculpture’s stalk–like ‘neck’. It is a seemingly mobile, menacing object, yet, is crushed against the ground and almost unidentifiable. Limbs lose their form, a leg becomes a carapace, an arm an insect's wing. It is at once human and female (with legs and breasts), animal (spider, snake, scorpion, praying mantis) and vegetable (leaf, stem, husk). Caught in a process of metamorphosis, the figure is wholly alien.

The work is the result of Giacometti’s longstanding obsession – part attraction, part repulsion – not only with spiders, but also with scenes of violent, sadistic crimes, which was an interest shared by many of the surrealists.

André Masson

1896, Balagny-sur-Therain, France – 1987, Paris, France

Le labyrinthe 1938

Oil on canvas

120 x 61cm

Gift of Basil and Elisa Goulandris 1982

AM 1982-46

© Andre Masson/ADAGP.

Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney, 2011

The ancient Greek myth of the Minotaur – the half–man, half–bull dwelling within a labyrinth – was a rich source of inspiration for the surrealists. It also inspired both the title and motif of the main surrealist journal of the mid 1930s. As a metaphor for the subconscious, the Minotaur signifies the repressed, instinctual aspects of human desire found in the darkest place of the conscious mind.

In the myth, the Cretan king ordered the Athenian artisan Daedalus to design a labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur; it was where he and his son Icarus would also be confined. Daedalus made wings of feathers and wax, so he and Icarus could fly to make their escape; however, Icarus flew too close to the sun and the wax melted, causing him to fall into the sea and drown.

In Masson’s painting, an inversion of the myth is depicted. The labyrinth has been eaten by the Minotaur – absorbed into the creature as an internal structure, with birds’ feathers, flowers, webs and leaves occupying the place of skeleton and organs. Masson’s Minotaur literally embodies a maze of passages and diversions, uniting the cerebral and the instinctual, or the physical self and the unconscious.

Please note: The videos featured in this virtual tour are available to Australian audiences only.

1929–1939 MENACING TIMES

The decade preceding World War Two was characterised by mounting tension and discontent in Europe. The effects of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 reverberated around the world, causing considerable financial hardship for millions, while totalitarian regimes came to power in many parts of Europe. In the face of this, Surrealism’s political intentions were subject to considerable scrutiny and internal questioning.

Salvador Dalí’s theory of ‘Paranoiac–Criticism’, which rejected political content in art in favour of the semi–conscious expression of subjective desires, was highly influential on Surrealism around 1930. In 1935, a split between André Breton and the French Communist Party directed Surrealism away from party political debates to focus on sexuality and desire. For the surrealists, the unconscious became the most likely site of revolution.

In the 1930s, Surrealism mounted an attack on traditional art forms like painting, which some felt was a medium appropriate for bourgeois drawing rooms, not for political struggle. Louis Aragon countered Breton’s elevation of surrealist painting, arguing instead for the primacy of collage; Max Ernst's collage–novel of 1929 La Femme 100 têtes was Aragon’s exemplar.

Another challenge to painting came in the form of the ‘surrealist object’. Neither sculptures nor found objects, these objects were considered to have ‘symbolic function’ rather than any aesthetic or formal quality. An exhibition of ‘surrealist objects’ held in Paris, in 1936, included Marcel Duchamp’s readymade Bottle rack 1914 and Alberto Giacometti’s Suspended ball 1930, alongside African and Oceanic masks.

The place of photography as an ideal medium for surrealist expression became prominent during this decade, with the work of Man Ray, Dora Maar, Hans Bellmer, Claude Cahun and Brassaï frequently featured in exhibitions and publications.

One of the three major journals that appeared during this period was DOCUMENTS, edited by Georges Bataille. The journaloffered an alternative philosophy to Breton’s Surrealism and focused on the darker aspects of the human psyche, in particular the subconscious ‘drives’ of sex and death.